Sunday 19 December 2010

From the "world turns into Daily Mail editorial" department.

And now on a more Right-wing tip: I met a teacher yesterday, who told me that her school has banned kids from going out in the snow, in case they hurt themselves; and banned conkers.

How Things Work

Step 1. Cadbury's chocolate poisons its customers with salmonella.

Step 2. Cadbury's moves its factory to Poland.

Step 3. Cadbury's brings out a chocolate bar with Union Jack packaging.

... and now a tax coda...

Step 4. Cadbury's creates a subsidiary in Ireland to take advantage of its 10% tax, and fights the UK government in the European Court of Justice.

Step 2. Cadbury's moves its factory to Poland.

Step 3. Cadbury's brings out a chocolate bar with Union Jack packaging.

... and now a tax coda...

Step 4. Cadbury's creates a subsidiary in Ireland to take advantage of its 10% tax, and fights the UK government in the European Court of Justice.

Sunday 28 November 2010

Sunday 14 November 2010

And on the subject of international mobility...

... here's another story about young people getting out of Ireland.

Most people's sympathies will be more with the unsatisfied young emigrants than with Vodafone. The generation above them spent irresponsibly on both private and public goods. (Distribute the blame between private and public, according to your own political preferences.) Now the young are expected to pay for it.

Some libertarians see mobility ("voting with your feet") as a substitute for the failings of democracy. They can even get a bit utopian about it. This idea does not work so well if societies have to make investments over time. For then, people may exit during the hard times when society invests for the future, and return during the easy times when the investment pays off. Mobility can also damage the "social contract" whereby young workers pay the pensions of the old, and expect to be paid for in their turn.

(Technical note: in theory, all these problems may be soluble with individualised funded pensions and with government debt to smooth consumption. In theory is the operative phrase. Real societies aren't like that.)

Ireland is a small country with a history of emigration. Crises may be made worse if the young and talented rush for the exit. Positive conclusion: small is not always beautiful.

Normative conclusion: a country is not just a bag to store capital and labour. Concordia parvae res crescunt, discordia maximae dilabuntur ;-)

Most people's sympathies will be more with the unsatisfied young emigrants than with Vodafone. The generation above them spent irresponsibly on both private and public goods. (Distribute the blame between private and public, according to your own political preferences.) Now the young are expected to pay for it.

Some libertarians see mobility ("voting with your feet") as a substitute for the failings of democracy. They can even get a bit utopian about it. This idea does not work so well if societies have to make investments over time. For then, people may exit during the hard times when society invests for the future, and return during the easy times when the investment pays off. Mobility can also damage the "social contract" whereby young workers pay the pensions of the old, and expect to be paid for in their turn.

(Technical note: in theory, all these problems may be soluble with individualised funded pensions and with government debt to smooth consumption. In theory is the operative phrase. Real societies aren't like that.)

Ireland is a small country with a history of emigration. Crises may be made worse if the young and talented rush for the exit. Positive conclusion: small is not always beautiful.

Normative conclusion: a country is not just a bag to store capital and labour. Concordia parvae res crescunt, discordia maximae dilabuntur ;-)

Vodafone, globalization and taxation

Globalization skeptics argue that tax rates for capital haven't gone down very much as a result of increased capital mobility. Stories like this one suggest that they ought to focus their attention specifically on multinationals. Nick Cohen has a thoughtful take on the issue.

I am slightly more sympathetic to Dave Hartnett. If you are aiming to maximize the government's tax revenue, you probably would like the ability to negotiate with big multinational companies. Treating them the same as everyone else might just lead them to move elsewhere. On the other hand, there is a rules-versus-discretion issue: a reputation for being flexible on tax may lead other companies to demand special deals. Also, as Mr Cohen points out, the moral effects are not good.

I am slightly more sympathetic to Dave Hartnett. If you are aiming to maximize the government's tax revenue, you probably would like the ability to negotiate with big multinational companies. Treating them the same as everyone else might just lead them to move elsewhere. On the other hand, there is a rules-versus-discretion issue: a reputation for being flexible on tax may lead other companies to demand special deals. Also, as Mr Cohen points out, the moral effects are not good.

Saturday 13 November 2010

Sunday 7 November 2010

Inflation

Everyone is discussing whether central banks' policies (low interest rates, quantitative easing) will increase inflation. At the moment headline inflation rates are low, so the inflation doves are winning the argument.

Before the crisis, there was a similar argument. Then optimists pointed to low headline inflation rates to show that we couldn't be in a bubble. But house prices aren't included in headline inflation. There was massive inflation there. Could the same thing be happening now? Obviously the house price bubble has not yet come back, but central bank policy could be sustaining prices at higher levels than they would otherwise be, and laying the foundations for another asset-price boom.

More generally, could it be that low interest rates act as a transfer to the mortgage-owning median voter?

Just asking, because my ignorance of macroeconomics is profound.

Before the crisis, there was a similar argument. Then optimists pointed to low headline inflation rates to show that we couldn't be in a bubble. But house prices aren't included in headline inflation. There was massive inflation there. Could the same thing be happening now? Obviously the house price bubble has not yet come back, but central bank policy could be sustaining prices at higher levels than they would otherwise be, and laying the foundations for another asset-price boom.

More generally, could it be that low interest rates act as a transfer to the mortgage-owning median voter?

Just asking, because my ignorance of macroeconomics is profound.

Friday 22 October 2010

I need a Hiwi

Where have all my subjects gone?

Where are the public goods?

I need a uniform variable

To calculate the odds

Isn’t there a white knight to program in zTree

Late at night at the MPI I dream of what I need

I need a Hiwi

I’m holding on for a Hiwi ‘til the treatment is right

He’s gotta be pale

And he’s gotta have specs

And just run the code once more tonight

I need a Hiwi

I’m holding on for a Hiwi till the screens all look tight

He’s gotta be thin

And to mainline caffeine

I need a Hiwi...

Where are the public goods?

I need a uniform variable

To calculate the odds

Isn’t there a white knight to program in zTree

Late at night at the MPI I dream of what I need

I need a Hiwi

I’m holding on for a Hiwi ‘til the treatment is right

He’s gotta be pale

And he’s gotta have specs

And just run the code once more tonight

I need a Hiwi

I’m holding on for a Hiwi till the screens all look tight

He’s gotta be thin

And to mainline caffeine

Cos he’s gotta be working all night

Somewhere after midnight

At the ESI group, floor 3,

Somewhere just beyond my reach

There’s a random match for me

Testing and retesting, drinking coffee by the mug

It’s gonna take a superman to get this code debugged!

I need a Hiwi

I’m holding on for a Hiwi ‘til the treatment is right

He’s gotta be pale

And he’s gotta have specs

And his skin should be whiter than white

Somewhere after midnight

At the ESI group, floor 3,

Somewhere just beyond my reach

There’s a random match for me

Testing and retesting, drinking coffee by the mug

It’s gonna take a superman to get this code debugged!

I need a Hiwi

I’m holding on for a Hiwi ‘til the treatment is right

He’s gotta be pale

And he’s gotta have specs

And his skin should be whiter than white

I need a Hiwi

I’m holding on for a Hiwi cos my pilot was shite

He’s gotta be thin

And he’s gotta stay in,

Yeah, he mustn't go out in sunlight

Up by the server in the Galerie lab

Out where the lightning splits ORSEE

I could swear there is someone out there

Watching me

Through the wind and the chill and the rain

And the flood and the storm

I can feel his approach

Like the subjects at the door

(Like the subjects at the door)

He’s gotta be thin

And he’s gotta stay in,

Yeah, he mustn't go out in sunlight

Up by the server in the Galerie lab

Out where the lightning splits ORSEE

I could swear there is someone out there

Watching me

Through the wind and the chill and the rain

And the flood and the storm

I can feel his approach

Like the subjects at the door

(Like the subjects at the door)

(Like the subjects at the door)

I need a Hiwi...

With apologies to Bonnie Tyler, and love and respect to the Hilfswissenschaftler of ESI Group.

Wednesday 20 October 2010

Sunday 17 October 2010

Defending Nick Clegg

More on education, following on from a Facebook discussion. Most people around me think that the tuition fees increase is a betrayal of Lib Dem ideals. Well, it sure wasn't in their manifesto... but more broadly, I disagree.

The biggest argument against tuition fees is that they will discourage poor people from going to university. I can't prove this won't happen, but it really has to be a psychological argument. Whether you are poor or rich, if you will get cheap loans to go to university, and have the capacity to do so, it is an insanely good deal, at £7000 a year or at £3000 a year. On average, the increase in your income will pay for itself many times over. So the story has to be: people will be scared off by the sheer amount of debt, and the uncertainty involved. That could be true. People are not perfectly rational calculators, and large debts can be frightening (except to all those geniuses in the City). However, it seems less likely to be a permanent effect. When people get used to the idea of large student loans, and when they see others using them, they will no longer seem so frightening. In particular, the US, which funded university via loans, had a high proportion of people going to college long before most of Europe did. That suggests that loans do not have to scare people off. (My friend Luke made the point that US education was boosted by the free university places given to WWII and Vietnam vets. It is an interesting story. The original GI bill put 8 million people through college. But it seems more likely to provide a kickstart than to have sustained high US college enrolment over the whole postwar period.)

What if you are poor but want to do something idealistic rather than making pots of extra money from your university education? You might then be put off, and either skip university or choose a money-making career. This would be unfair to you, and would also deprive the UK of the benefits of people who do idealistic but low-paid jobs like teaching or social work.

Well, it has to be a very idealistic job for it still not to benefit you to go to university. I am an academic, which is quite idealistic... oh go on, it is. But I will still earn much, much more over my lifetime than if I hadn't gone to university. (Back of the envelope calculation: half a million more.) That holds also for Luke, who is a teacher, or Kemal, who works in a development organization. If you are planning to be Mother Teresa, then yes, you could be put off by debt. But most people do not volunteer all their lives.

There are too few people from poor backgrounds going to university. But what causes this? My hunch is that it is that many people know they would not get accepted at a university, and/or would not be able to benefit from it. For example, you will not get much from university if you cannot write an undergraduate essay. Unfortunately, many 18-year-olds can't. Perhaps some of this is down to natural inequalities in intelligence. But surely a lot of it is down to problems in the education system before university. If you have not been well taught at school, then you won't get a university place. In fact, even in the golden days of free education, the educational inequalities existed (see Figure 3 on page 6). And a study of the original introduction of tuition fees suggests: "much of the impact from social class on university attendance actually occurs well before entry into HE."

If so, then the best way to get equal access to university is to improve the quality of pre-university education, especially for the poorest. That seems to be the idea behind the pupil premium. The Lib Dems will probably get slaughtered over the tuition fees increase. That's a shame, because Nick Clegg is trying to do the right thing.

The biggest argument against tuition fees is that they will discourage poor people from going to university. I can't prove this won't happen, but it really has to be a psychological argument. Whether you are poor or rich, if you will get cheap loans to go to university, and have the capacity to do so, it is an insanely good deal, at £7000 a year or at £3000 a year. On average, the increase in your income will pay for itself many times over. So the story has to be: people will be scared off by the sheer amount of debt, and the uncertainty involved. That could be true. People are not perfectly rational calculators, and large debts can be frightening (except to all those geniuses in the City). However, it seems less likely to be a permanent effect. When people get used to the idea of large student loans, and when they see others using them, they will no longer seem so frightening. In particular, the US, which funded university via loans, had a high proportion of people going to college long before most of Europe did. That suggests that loans do not have to scare people off. (My friend Luke made the point that US education was boosted by the free university places given to WWII and Vietnam vets. It is an interesting story. The original GI bill put 8 million people through college. But it seems more likely to provide a kickstart than to have sustained high US college enrolment over the whole postwar period.)

What if you are poor but want to do something idealistic rather than making pots of extra money from your university education? You might then be put off, and either skip university or choose a money-making career. This would be unfair to you, and would also deprive the UK of the benefits of people who do idealistic but low-paid jobs like teaching or social work.

Well, it has to be a very idealistic job for it still not to benefit you to go to university. I am an academic, which is quite idealistic... oh go on, it is. But I will still earn much, much more over my lifetime than if I hadn't gone to university. (Back of the envelope calculation: half a million more.) That holds also for Luke, who is a teacher, or Kemal, who works in a development organization. If you are planning to be Mother Teresa, then yes, you could be put off by debt. But most people do not volunteer all their lives.

There are too few people from poor backgrounds going to university. But what causes this? My hunch is that it is that many people know they would not get accepted at a university, and/or would not be able to benefit from it. For example, you will not get much from university if you cannot write an undergraduate essay. Unfortunately, many 18-year-olds can't. Perhaps some of this is down to natural inequalities in intelligence. But surely a lot of it is down to problems in the education system before university. If you have not been well taught at school, then you won't get a university place. In fact, even in the golden days of free education, the educational inequalities existed (see Figure 3 on page 6). And a study of the original introduction of tuition fees suggests: "much of the impact from social class on university attendance actually occurs well before entry into HE."

Thursday 14 October 2010

3. The Eastern Pamir

In the East it's high up and harder to breathe. The country turns from green to absolute desert. There is not much vegetation. Little marmots occasionally run for the cover of their holes. Before they dive in they pause and look around – apparently this behaviour is instinctive, so this is how you can shoot them.

Our first night was in a yurt. These are big tents made of wood and covered in felt, warmed by stoves which seem to come from the 19th century and which are fed by yak and cow dung. There's a hole in the middle of the roof for the chimney: in the day this also lets light in but at night it's covered. A lot of the yurts we saw had solar panels attached, made, like most things in Tajikistan, in China, and providing enough electricity to power a TV and DVD. (Conversation of one nomadic, yak-herding yurt owner: “What do you think of Avatar? I haven't seen it yet.”)

When we arrived at the yurt, the owner's wife was milking a yak, so I asked if I could have a go. It is harder than it looks. The myth that yak milk is pink is untrue. (Maybe it's pink if you go higher in the mountains.) At night I went out to see the stars. Last time I saw the Milky Way properly, I was 18 and in India. I slept well in yurts: it feels nice to be close to the ground.

Next day we arrived in Murghab, a tiny market town of bare white walls. The Kyrgyz' tall white felt hats add to the atmosphere. We spent a lot of time casting roles for a Tajikistan spaghetti Western. Our driver Omur lived here, so we stayed with him.

We headed out to trek next morning. Losing the path on the way up to a pass, we scrambled up the mountainside. The climb was physically easy but the air was so thin – we were at about 4700 m – that we had to stop and catch our breath every minute. The mountain got steeper and steeper, with shale breaking off in our hands. Looking down became unpleasant. When we made it to the top I was as pale as a ghost. This was the time I felt most scared on the journey. We ate biscuits, drank Iranian fruit juice and admired the indescribably magnificent view over the next valley.

Over the next days we headed North to the border and said goodbye to Alessia and Davide. They were great travelling companions. On hearing that he would be sleeping in a yurt, Davide had remarked that he would need a yak to stay warm, to which Alessia replied with the immortal words

To make up numbers we picked up Daragh, an Irish guy who had been teaching in China for a year. He spoke Uighur (and hence other Turkic languages like Kyrgyz). We headed South again, stayed one more night in a yurt, and then made our way back to Khorog.

In Khorog we tried to get a plane back to Dushanbe. It was heavily oversubscribed (you just turn up and queue, there are no bookings). At one point our fixer said he would try and get us a lift on the army helicopter. Arianna turned pale but was eventually persuaded that this would ROCK. Alas, the army didn't want to take non-nationals for fear of questions from the KGB. (Yes, Tajikistan still has its own KGB.) Instead, we stayed one more night at a homestay. This was a fabulous place run by a family who were reminiscent of Giles' cartoons. They wore something turquoise, colour-coordinating with the apartment. The grandmother ruled the roost and cooked fabulous meals. There was an aunt who was constantly fighting with the uncle; a downtrodden sister who swept up; and the granddaughter, a schoolgirl in Dushanbe, who told us “all my friends are so Emo! [mimes wrist-cutting]”. Youth culture is truly universal.

Our first night was in a yurt. These are big tents made of wood and covered in felt, warmed by stoves which seem to come from the 19th century and which are fed by yak and cow dung. There's a hole in the middle of the roof for the chimney: in the day this also lets light in but at night it's covered. A lot of the yurts we saw had solar panels attached, made, like most things in Tajikistan, in China, and providing enough electricity to power a TV and DVD. (Conversation of one nomadic, yak-herding yurt owner: “What do you think of Avatar? I haven't seen it yet.”)

When we arrived at the yurt, the owner's wife was milking a yak, so I asked if I could have a go. It is harder than it looks. The myth that yak milk is pink is untrue. (Maybe it's pink if you go higher in the mountains.) At night I went out to see the stars. Last time I saw the Milky Way properly, I was 18 and in India. I slept well in yurts: it feels nice to be close to the ground.

Next day we arrived in Murghab, a tiny market town of bare white walls. The Kyrgyz' tall white felt hats add to the atmosphere. We spent a lot of time casting roles for a Tajikistan spaghetti Western. Our driver Omur lived here, so we stayed with him.

We headed out to trek next morning. Losing the path on the way up to a pass, we scrambled up the mountainside. The climb was physically easy but the air was so thin – we were at about 4700 m – that we had to stop and catch our breath every minute. The mountain got steeper and steeper, with shale breaking off in our hands. Looking down became unpleasant. When we made it to the top I was as pale as a ghost. This was the time I felt most scared on the journey. We ate biscuits, drank Iranian fruit juice and admired the indescribably magnificent view over the next valley.

Over the next days we headed North to the border and said goodbye to Alessia and Davide. They were great travelling companions. On hearing that he would be sleeping in a yurt, Davide had remarked that he would need a yak to stay warm, to which Alessia replied with the immortal words

“I don't need a yak. I have Davide.”This inspired the writing of a Yak Song, celebrating the tender bond between a woman and her yak. One recording is still extant.

To make up numbers we picked up Daragh, an Irish guy who had been teaching in China for a year. He spoke Uighur (and hence other Turkic languages like Kyrgyz). We headed South again, stayed one more night in a yurt, and then made our way back to Khorog.

In Khorog we tried to get a plane back to Dushanbe. It was heavily oversubscribed (you just turn up and queue, there are no bookings). At one point our fixer said he would try and get us a lift on the army helicopter. Arianna turned pale but was eventually persuaded that this would ROCK. Alas, the army didn't want to take non-nationals for fear of questions from the KGB. (Yes, Tajikistan still has its own KGB.) Instead, we stayed one more night at a homestay. This was a fabulous place run by a family who were reminiscent of Giles' cartoons. They wore something turquoise, colour-coordinating with the apartment. The grandmother ruled the roost and cooked fabulous meals. There was an aunt who was constantly fighting with the uncle; a downtrodden sister who swept up; and the granddaughter, a schoolgirl in Dushanbe, who told us “all my friends are so Emo! [mimes wrist-cutting]”. Youth culture is truly universal.

Sunday 3 October 2010

I left Germany!

I had a really happy two years in Jena. The people there are an incredibly nice and warm-hearted bunch. The MPI is a great research environment. I will miss you all!

Wednesday 22 September 2010

2. The Bartang and the Wakhan

In Khorog we fixed ourselves up with two other Italians to share a UAZ jeep down the Wakhan valley. Before meeting them we decided to hike up the Bartang valley for a day or two. This involved negotiating a ride in a Chinese-made Cherry minivan. We ended up paying about double the local price, which isn't really so bad a deal. The drive up the Bartang was beautiful but hair-raising. Sometimes the van felt as if it would fall over sideways, sometimes we had to get out and clear stones from the road, and once we were the first to test a newly-rebuilt wooden bridge. When we got out, one of our fellow passengers invited us into her cousin's house and we had our first taste of Tajik hospitality. Marifat spoke good English (and Russian and Pamiri and some Tajik) and was trying to find a job in Khorog.

We walked up the valley towards Ravmeddra, but by now it was late and we started to look for a house which was supposed to be open for hikers. Surely the one with no door and nothing but straw inside wasn't it. An hour later, as night fell on the steep and narrow path, we decided that probably was it and headed back there. We lit a small fire and fell asleep, woken only by the occasional bat and by the lumps in our backs, which Arianna described as "Tajik stone massage".

In the morning, we found ourselves in a deserted village. A local guy came by to gather hay. We couldn't communicate much but when Arianna said she came from Italy he smiled and said "Berlusconi!"

We got back later that day, stopping only for a couple of hours with the local police, who had a disagreement with our driver, and met our Italians that night. Davide and Alessia had been working in the embassy in Afghanistan and had got married in Kabul. (Most travellers in Tajikistan work in development of one kind or another... or are mountaineers or serious trekkers.) We asked them about Afghanistan. They were very informative, and very pessimistic. Bullet points: everything has got worse since the fraudulent presidential election; the Taliban control about 60% of the countryside; there are no good solutions.

Next day we set off. Our redoubtable jeep driver was called Omur. Lots of people report driver nightmares. We must have been lucky: Omurbek* is fast, safe and knows everything about the area. He is also quite a cool dude and has a great cowboy hat. Omur lives in Murghab and is ethnically Kyrgyz, like most people in the Eastern Pamirs.

The Wakhan valley runs down the Tajikistan-Afghan border. Like all the Pamirs (valleys) in the region it has its own language; these split off from each other before the European languages did. The Wakhan language is called -- what else? -- Wakhi. Under the Soviets people learned Russian. Now there is a push to teach Tajik: not necessarily an improvement, in the eyes of many.

Our first stop was in Ishkashim, in a homestay that was well on the way to being a proper hostel. In the morning we visited the Afghan market, which is held right on the border under the auspices of the Tajik police. (Exciting moment: seeing your mobile picking up an Afghan network.) The Afghans made the Tajiks, with their Western hairstyles and jeans, look rich. Then we rocked on down the valley, stopping at hot springs, fortresses complete with modern anti-personnel mines, and Buddhist temples, until we reached Langar. That was the first night you could really see the stars.

* -bek means something like "Mr."

Thursday 16 September 2010

A moral victory

In Tajikistan, I argued with Arianna about Europe versus the US. It's an old chestnut. Arianna thinks the US is a hideous capitalist maw where the poor sell their kids to Walmart as frozen turkeys. I know the truth -- the US is a glorious country of Freedom, unlike Europe which is inevitably doomed to Euro-Islamo-welfaro-infertili-sclerosis. So, in the spirit of Rousseau's remark in the Social Contract --

"What is the end of political association? The preservation and prosperity of its members. And what is the surest mark of their preservation and prosperity? Their numbers and population."*

-- I bet her that there were more immigrants from the EU to the US than vice versa. "No way", she said. "Five times more", I said, as a proportion of the source area's population. And we bet a dinner on it.

The best estimates of migrant stocks I know come from the Global Migrant Origin Database, which comes out of Sussex IIRC. Actually, for our purposes, OECD stats would be fine. We did the calculations today while waiting for our follow-up vaccinations. (PS: Arianna, Malta is so in the EU; others, therefore these calculations are slightly inaccurate.)

TOTAL IMMIGRANTS FROM EU-27 TO US: 4 730 294.

Divided by EU population, which can't possibly be more than 500 million, so let's say it is that: 0.9%. (Actually, according to Eurostat, it is almost exactly 500 million.)

TOTAL IMMIGRANTS FROM US TO EU-27 ... 571 706. Accidentally including Croatia.

Divided by US population of about 300 million: a paltry 0.19%.

OK, not five times, but four times. I owe you dinner, but the moral victory is mine!

(NB also: not much is changed by excluding Eastern Europe.)

* though Rousseau excluded "naturalisation or colonies" as external aids.

"What is the end of political association? The preservation and prosperity of its members. And what is the surest mark of their preservation and prosperity? Their numbers and population."*

-- I bet her that there were more immigrants from the EU to the US than vice versa. "No way", she said. "Five times more", I said, as a proportion of the source area's population. And we bet a dinner on it.

The best estimates of migrant stocks I know come from the Global Migrant Origin Database, which comes out of Sussex IIRC. Actually, for our purposes, OECD stats would be fine. We did the calculations today while waiting for our follow-up vaccinations. (PS: Arianna, Malta is so in the EU; others, therefore these calculations are slightly inaccurate.)

TOTAL IMMIGRANTS FROM EU-27 TO US: 4 730 294.

Divided by EU population, which can't possibly be more than 500 million, so let's say it is that: 0.9%. (Actually, according to Eurostat, it is almost exactly 500 million.)

TOTAL IMMIGRANTS FROM US TO EU-27 ... 571 706. Accidentally including Croatia.

Divided by US population of about 300 million: a paltry 0.19%.

OK, not five times, but four times. I owe you dinner, but the moral victory is mine!

(NB also: not much is changed by excluding Eastern Europe.)

* though Rousseau excluded "naturalisation or colonies" as external aids.

Bullshit from many angles

Some facts about the THES universities rankings story, in case anyone in the UK was wondering.

- Five out of the top fifty universities is a pretty good score, given that we have about 5% of total OECD population.

- If your universities slide in a single year, this is unlikely to be due to a sudden collapse in quality. It is more likely because the ranking method has changed, which is just what happened in this case.

- It seems exaggerated to call the THES rankings "the major global benchmark of worldwide university performance", as the THES editor does.There are several different rankings out there. The most respected, I would say, is the Academic Ranking of World Universities published by Shanghai Jiao Tong university. In the 2010 version, the UK gets five out of the top fifty spots... and the same number in 2009... and in 2008.

- Previous THES rankings seemed crazily pro-UK to me. Four out of the top ten universities in the world? Seventeen in the top 100, with the University of Manchester beating UCLA, and Bristol beating Northwestern and Berkeley? I don't find that plausible.

Wednesday 15 September 2010

1. Dushanbe to Khorog

When we arrived at Dushanbe airport, the scary plane ride to Khorog wasn't going, so made our way to the taxi station where you can hire 4WDs for the journey. The station was dusty, dirty and poor, with a store selling biscuits and tea, and the first of many very disgusting toilets. I felt happy as soon as I got there.

We cut a deal for 150 Somani (35 EUR) per person to go in the back of a Mitsubishi Pajero. The hierarchy of 4WDs is, in ascending order:

Tajik roads are dreadful. At best they are like a very old English country lane. At worst, it is more comfortable to drive off-road: the bumps in the road are harder to anticipate. After a few days, we got used to constantly being shaken up and down, and it became oddly soothing.

We got to Khorog in 15 hours, which the guys at the guesthouse said was an incredibly good time. Every few hours we stopped to stretch our legs and buy fruit from village kids, or eat. It was Ramadan, but you don't need to fast if you are traveling: despite this, one of our fellow-passengers did. He was a Tajik returning from Moscow. Emigration to Russia for work is common in all the stans, and a lot of people bemoan the brain drain.

A lot of the road passes along the Afghan border, which is formed by the Amu-Darya (Oxus) river. The difference is striking: Tajikistan seems poor, but it has roads and electricity. Afghanistan looks unchanged since the middle ages.

We arrived at the very nice Pamir Lodge, around midnight, and got the last free room. In the morning, Khorog looked poor and messy. (But next time we arrived, on our way back from Murghab, it would seem large, rich and colourful.)

We cut a deal for 150 Somani (35 EUR) per person to go in the back of a Mitsubishi Pajero. The hierarchy of 4WDs is, in ascending order:

- UAZ (pronounced Wox) - basic green Soviet-era jeeps, but very fixable

- Pajero

- Toyota Landcruiser

Tajik roads are dreadful. At best they are like a very old English country lane. At worst, it is more comfortable to drive off-road: the bumps in the road are harder to anticipate. After a few days, we got used to constantly being shaken up and down, and it became oddly soothing.

We got to Khorog in 15 hours, which the guys at the guesthouse said was an incredibly good time. Every few hours we stopped to stretch our legs and buy fruit from village kids, or eat. It was Ramadan, but you don't need to fast if you are traveling: despite this, one of our fellow-passengers did. He was a Tajik returning from Moscow. Emigration to Russia for work is common in all the stans, and a lot of people bemoan the brain drain.

A lot of the road passes along the Afghan border, which is formed by the Amu-Darya (Oxus) river. The difference is striking: Tajikistan seems poor, but it has roads and electricity. Afghanistan looks unchanged since the middle ages.

We arrived at the very nice Pamir Lodge, around midnight, and got the last free room. In the morning, Khorog looked poor and messy. (But next time we arrived, on our way back from Murghab, it would seem large, rich and colourful.)

Thursday 19 August 2010

New work in progress up: "Group Reciprocity"

We've got a first draft of the paper on Group Reciprocity up. I blogged about the results from the first experimental session before. The end results aren't quite so strong but are still interesting.

Experimental economists have worked a lot on reciprocity: when you harm (or help) me, I harm (help) you back. Group reciprocity adds a twist: you harm me, so I want to harm somebody else in your group. Group could be almost anything: gender, ethnicity, football team supporters ....

Group reciprocity might be an important cause of things like war, ethnic tension and racial discrimination, so it would be useful if we could study it in the lab. The paper is a first attempt to do that. I think there's still a lot more to be done.

Experimental economists have worked a lot on reciprocity: when you harm (or help) me, I harm (help) you back. Group reciprocity adds a twist: you harm me, so I want to harm somebody else in your group. Group could be almost anything: gender, ethnicity, football team supporters ....

Group reciprocity might be an important cause of things like war, ethnic tension and racial discrimination, so it would be useful if we could study it in the lab. The paper is a first attempt to do that. I think there's still a lot more to be done.

|

| Atlanta Race Riot 1906 |

Friday 13 August 2010

Calculating the standard error of marginal effects using the delta method, in R

Here's a little piece of code I used to calculate marginal effects on probabilities in a non-linear (bivariate probit) model, using the Delta Method.

Warning: I am not a proper statistician. Use at your own risk!

# needed for a multivariate normal distribution

library(mvtnorm)

# bv is a vector of betas

# this calculates the change in predicted probabilities

f <- function (bv) {

rho <- rhobit(bv[3], inverse=T)

p <- array(dim=c(2,2,2))

for (c1 in 0:1) {

for (c2 in 0:1) {

for (d_o in 0:1) {

sgn1 <- 2*c1 - 1

sgn2 <- 2*c2 - 1

############################################

p[c1+1,c2+1,d_o+1] <- pmvnorm(upper=c(sgn1*(bv[1]+bv[4]*d_o),sgn2*(bv[2]+bv[5]*d_o)), corr=matrix(c(1,sgn1*sgn2*rho,sgn1*sgn2*rho,1), nrow=2))

}

}

}

# I use the global firstdec so that the function conforms to what grad() expects

# the total probability of choosing 1 for either the first

# or the second decision:

if (firstdec) p[2,2,2]+p[2,1,2]-p[2,2,1]-p[2,1,1] else p[2,2,2]+p[1,2,2]-p[2,2,1]-p[1,2,1]

}

firstdec <- TRUE

pred[1] <- f(coef(mbvp.1))

gradient <- grad(f, coef(mbvp.1))

# ===== this is the delta method ====

predse[1] <- sqrt(gradient %*% vcov(mbvp.1) %*% gradient)

firstdec <- FALSE

pred[2] <- f(coef(mbvp.1))

gradient <- grad(f, coef(mbvp.1))

predse[2] <- sqrt(gradient %*% vcov(mbvp.1) %*% gradient)

margprobs <- cbind(pred, se=predse, Z=pred/predse, p=2*pnorm(-abs(pred/predse)))

print(margprobs, digits=3)

Warning: I am not a proper statistician. Use at your own risk!

# to create the model:

library(VGAM)

mbvp.1 <- vglm(cbind(decision_matrices.1-1, decision_matrices.6-1) ~ defect_other, binom2.rho, data=ds, trace=TRUE)

mbvp.1 <- vglm(cbind(decision_matrices.1-1, decision_matrices.6-1) ~ defect_other, binom2.rho, data=ds, trace=TRUE)

# needed to compute the gradient of my function numerically

library(numDeriv)# needed for a multivariate normal distribution

library(mvtnorm)

# bv is a vector of betas

# this calculates the change in predicted probabilities

f <- function (bv) {

rho <- rhobit(bv[3], inverse=T)

p <- array(dim=c(2,2,2))

for (c1 in 0:1) {

for (c2 in 0:1) {

for (d_o in 0:1) {

sgn1 <- 2*c1 - 1

sgn2 <- 2*c2 - 1

############################################

# the probability of making choice (c1,c2)

# when the independent variable

# defect_other=d_o:############################################

p[c1+1,c2+1,d_o+1] <- pmvnorm(upper=c(sgn1*(bv[1]+bv[4]*d_o),sgn2*(bv[2]+bv[5]*d_o)), corr=matrix(c(1,sgn1*sgn2*rho,sgn1*sgn2*rho,1), nrow=2))

}

}

}

# I use the global firstdec so that the function conforms to what grad() expects

# the total probability of choosing 1 for either the first

# or the second decision:

if (firstdec) p[2,2,2]+p[2,1,2]-p[2,2,1]-p[2,1,1] else p[2,2,2]+p[1,2,2]-p[2,2,1]-p[1,2,1]

}

firstdec <- TRUE

pred[1] <- f(coef(mbvp.1))

gradient <- grad(f, coef(mbvp.1))

# ===== this is the delta method ====

predse[1] <- sqrt(gradient %*% vcov(mbvp.1) %*% gradient)

firstdec <- FALSE

pred[2] <- f(coef(mbvp.1))

gradient <- grad(f, coef(mbvp.1))

predse[2] <- sqrt(gradient %*% vcov(mbvp.1) %*% gradient)

margprobs <- cbind(pred, se=predse, Z=pred/predse, p=2*pnorm(-abs(pred/predse)))

print(margprobs, digits=3)

Sunday 1 August 2010

Saturday 31 July 2010

Very interesting discussion about academia

... over at The Atlantic.

My tuppenorth:

My tuppenorth:

- at least half the added value of university for undergraduates is the other undergraduates. If you hang around with clever, interesting people, that expands your brain - and most 18 year olds pay more attention to other 18 year olds than their professors, for some reason - plus, if your friends go on to be important and influential, then you have a network.

- this means that for universities, nothing succeeds like success. (Economic term: multiple equilibria.) No matter how good a community college's teaching, it will be less attractive than Harvard because Harvard has Harvard students.

- This gives famous universities the chance to extract rents: they can charge a lot more than they actually provide by way of teaching etc. You are paying for the name and the networking.

- These rents go into research.

- The authors are damn right that a lot of research is useless. The problem is, research is like advertising: half of the money spent on it is wasted, but nobody knows which half.

Friday 23 July 2010

A few tidbits from the pilot experiment

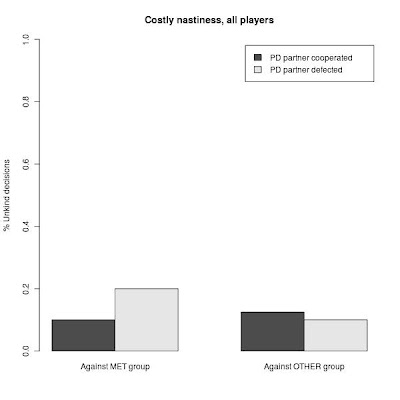

Subjects were divided into three groups. Each played a prisoner's dilemma against another subject from a different group (the "prisoner's dilemma partner" or "PD partner"). Then, each of them made a set of allocations between themselves and other subjects - who were identified by group and player number, but who were not the same as their PD partner.

We call the group of each subject's prisoner's dilemma partner the MET group; the third group is the OTHER group.

When the PD partner defected, subjects made more allocations that harmed the other player. This difference was larger when making allocations against others from the MET group:

The effect is clearer for subjects who had themselves cooperated in the prisoner's dilemma:

For some decisions, being nasty to the other player actually cost the subject money. Not surprisingly there were fewer of those allocations, but the same pattern is observed:

and again the pattern is even stronger for PD cooperators.

Of course this is just the pilot, and I haven't yet done any rigorous statistical significance tests.

We call the group of each subject's prisoner's dilemma partner the MET group; the third group is the OTHER group.

When the PD partner defected, subjects made more allocations that harmed the other player. This difference was larger when making allocations against others from the MET group:

The effect is clearer for subjects who had themselves cooperated in the prisoner's dilemma:

For some decisions, being nasty to the other player actually cost the subject money. Not surprisingly there were fewer of those allocations, but the same pattern is observed:

and again the pattern is even stronger for PD cooperators.

Of course this is just the pilot, and I haven't yet done any rigorous statistical significance tests.

Saturday 17 July 2010

Why don't evolutionary economists believe in equilibrium?

This is a provocative question for Arianna and others of her persuasion. Much of it goes over similar ground to Paul Samuelson's address to a conference of evolutionary economists a couple of years ago.

Evolutionary economics takes its cue from biology and sees the economy as an ecosystem, with an endless variety of different "species" (firm strategies) competing, right? And as a result EEers reject the rationalistic concept of equilibrium, whether market or game-theoretic. The world is always moving forward, never at rest, and behaviour is never perfectly adjusted between different actors.

I find these claims pretty plausible, and ironically more plausible in my field -- political economy, where straight Nash Equilibrium is completely dominant -- than in the study of markets.

But.

1. Biologists use equilibrium concepts all the time, and these concepts were adapted from game theory by John Maynard Smith. Indeed, instead of being looser than "rational" game theory, evolutionary game theory concepts actually make tighter predictions: an Evolutionarily Stable Strategy is always a Nash Equilibrium, but not the other way round.

2. Equilibrium has been tested in the lab, and holds up pretty well -- e.g. in auction markets. I am not claiming we can naively generalize from the lab to real markets. But if it works well in the lab, doesn't that support the underlying theory?

3. One major use of equilibrium predictions is to generate comparative statics (ie predictions that if parameter X varies, outcome variable Y will vary with it in some specific way). Even if economies never reach equilibrium, the forces pushing them towards equilibrium may still generate the same comparative statics. For example, although the voting behaviour that we observe is not compatible with the main equilibrium voting models -- people vote too much -- still, they vote less when the election is less competitive, as the models predict.

4. Social science is all about the search for surprising insights. Equilibrium concepts -- more fundamentally, the idea that people react to incentives -- are a good way to generate these insights. (One random example: smoking bans in pubs might increase child cancer, because more people stay at home and smoke there.)

So, what's wrong with equilibrium?

Evolutionary economics takes its cue from biology and sees the economy as an ecosystem, with an endless variety of different "species" (firm strategies) competing, right? And as a result EEers reject the rationalistic concept of equilibrium, whether market or game-theoretic. The world is always moving forward, never at rest, and behaviour is never perfectly adjusted between different actors.

I find these claims pretty plausible, and ironically more plausible in my field -- political economy, where straight Nash Equilibrium is completely dominant -- than in the study of markets.

But.

1. Biologists use equilibrium concepts all the time, and these concepts were adapted from game theory by John Maynard Smith. Indeed, instead of being looser than "rational" game theory, evolutionary game theory concepts actually make tighter predictions: an Evolutionarily Stable Strategy is always a Nash Equilibrium, but not the other way round.

2. Equilibrium has been tested in the lab, and holds up pretty well -- e.g. in auction markets. I am not claiming we can naively generalize from the lab to real markets. But if it works well in the lab, doesn't that support the underlying theory?

3. One major use of equilibrium predictions is to generate comparative statics (ie predictions that if parameter X varies, outcome variable Y will vary with it in some specific way). Even if economies never reach equilibrium, the forces pushing them towards equilibrium may still generate the same comparative statics. For example, although the voting behaviour that we observe is not compatible with the main equilibrium voting models -- people vote too much -- still, they vote less when the election is less competitive, as the models predict.

4. Social science is all about the search for surprising insights. Equilibrium concepts -- more fundamentally, the idea that people react to incentives -- are a good way to generate these insights. (One random example: smoking bans in pubs might increase child cancer, because more people stay at home and smoke there.)

So, what's wrong with equilibrium?

Monday 12 July 2010

New paper

There's a new work-in-progress on my website. It's with Ro'i Zultan and is called "Brothers in Arms: Cooperation in Defence". A poster is here.

We started this paper to try and resolve a puzzle in social science and biology. Often, unrelated individuals help each other when they face an external attacker. For example, an estimated 200,000 people were active members of the French Resistance in World War II. In the laboratory, we can observe a similar phenomenon under controlled conditions: cooperation increases in the presence of an external threat. Non-humans do it too. For instance, musk oxen band together to drive off wolves.

This is a puzzle because, economically, helping others seems to have costs but no benefits. Or, biologically speaking, this behaviour should decrease the fitness of the animals who display it.

We explain this cooperation by invoking signalling theory. Some groups are prepared to cooperate, for example because they are kin, or because they are in long-term cooperative relationships. Other groups consist of self-interested individuals. Attackers are strategic: they prefer to attack groups who will not help each other. (Think of the bandits in the Magnificent Seven.) If they start to think they are attacking a very cooperative group, they will look for another target. Then, even self-interested individuals have an incentive to help each other during an attack, as this will deter further attacks.

So far you might get with common sense. However, economists and others may be asking "surely the group's reputation for cooperativeness is a public good, just like defence itself, and will be underprovided". Here, our theoretical model shows one possible answer: the series of repeated attacks gives this public good a "weakest-link technology". That is, if you are the first person not to help during an attack, then the attacker immediately recognises that previous helping was fraudulent and can no longer be deterred. This in turn gives a strong incentive to help when it's your turn.

The paper is here.

We started this paper to try and resolve a puzzle in social science and biology. Often, unrelated individuals help each other when they face an external attacker. For example, an estimated 200,000 people were active members of the French Resistance in World War II. In the laboratory, we can observe a similar phenomenon under controlled conditions: cooperation increases in the presence of an external threat. Non-humans do it too. For instance, musk oxen band together to drive off wolves.

This is a puzzle because, economically, helping others seems to have costs but no benefits. Or, biologically speaking, this behaviour should decrease the fitness of the animals who display it.

We explain this cooperation by invoking signalling theory. Some groups are prepared to cooperate, for example because they are kin, or because they are in long-term cooperative relationships. Other groups consist of self-interested individuals. Attackers are strategic: they prefer to attack groups who will not help each other. (Think of the bandits in the Magnificent Seven.) If they start to think they are attacking a very cooperative group, they will look for another target. Then, even self-interested individuals have an incentive to help each other during an attack, as this will deter further attacks.

So far you might get with common sense. However, economists and others may be asking "surely the group's reputation for cooperativeness is a public good, just like defence itself, and will be underprovided". Here, our theoretical model shows one possible answer: the series of repeated attacks gives this public good a "weakest-link technology". That is, if you are the first person not to help during an attack, then the attacker immediately recognises that previous helping was fraudulent and can no longer be deterred. This in turn gives a strong incentive to help when it's your turn.

The paper is here.

Saturday 10 July 2010

At the demo

Arianna persuaded me to go to the anti-Nazi demo in Gera today. The local fascists were having a sort of annual picnic.

Gera is quite pretty, not like the stereotype of a run-down East German town. If I were an artist I'd buy myself 1000 sq m of old warehouse, cheap as chips.

We avoided the Black Bloc, who looked like teenagers out for a fight, and joined the main crowd on the bridge. Tons of police. Some Christians playing samba. A couple of guys doing capoeira. Soon th Nazis come across the bridge, under heavy police escort. They have to cross in single file, accompanied by our chants of "Nazis raus!" Most are big, tough, aggressive-looking guys. A few scrawny girls. They look as if they enjoy the hate, so is it really effective? Maybe the point is to make sure that people who don't enjoy the hate are put off.

We go and eat at the Sächsische Bahnhof, a cool place in a beautiful old run-down building. When we get back, the demo is gone and the Nazis are listening to speeches. The world Volk appears a lot. We must not allow our Volk to be destroyed!

East Germany is really not a multicultural place: I don't know what they are afraid of. As it happens, I think there are some legitimate reasons to worry about immigration. But actual anti-immigration sentiment always seems to be irrational and driven by primal human fear of strangers.

If this is Europe's biggest Nazi-fest as the flyers said, we have little to fear. There were maybe 1000 people there. The event was a bit smaller than Wivenhoe village fête.

The demo was supported by Die Linke, Germany's Left populist party. I think they are a much bigger threat to European democracy than the neo-Nazis. But they play by democratic rules so they have to be tolerated. And the populist threat is not just from the Left. The French assembly is preparing to ban the Burqa. This is a direct assault on liberal freedoms. But some people misguidedly support it because of an ill-thought-out feminism. Have I quoted J S Mill before? Never mind: "His own good, whether physical or moral, is not a sufficient warrant."

Gera is quite pretty, not like the stereotype of a run-down East German town. If I were an artist I'd buy myself 1000 sq m of old warehouse, cheap as chips.

We avoided the Black Bloc, who looked like teenagers out for a fight, and joined the main crowd on the bridge. Tons of police. Some Christians playing samba. A couple of guys doing capoeira. Soon th Nazis come across the bridge, under heavy police escort. They have to cross in single file, accompanied by our chants of "Nazis raus!" Most are big, tough, aggressive-looking guys. A few scrawny girls. They look as if they enjoy the hate, so is it really effective? Maybe the point is to make sure that people who don't enjoy the hate are put off.

We go and eat at the Sächsische Bahnhof, a cool place in a beautiful old run-down building. When we get back, the demo is gone and the Nazis are listening to speeches. The world Volk appears a lot. We must not allow our Volk to be destroyed!

East Germany is really not a multicultural place: I don't know what they are afraid of. As it happens, I think there are some legitimate reasons to worry about immigration. But actual anti-immigration sentiment always seems to be irrational and driven by primal human fear of strangers.

If this is Europe's biggest Nazi-fest as the flyers said, we have little to fear. There were maybe 1000 people there. The event was a bit smaller than Wivenhoe village fête.

The demo was supported by Die Linke, Germany's Left populist party. I think they are a much bigger threat to European democracy than the neo-Nazis. But they play by democratic rules so they have to be tolerated. And the populist threat is not just from the Left. The French assembly is preparing to ban the Burqa. This is a direct assault on liberal freedoms. But some people misguidedly support it because of an ill-thought-out feminism. Have I quoted J S Mill before? Never mind: "His own good, whether physical or moral, is not a sufficient warrant."

Thursday 8 July 2010

CAP

OMG listen to this vile political gitweasel!

"In looking at the EU budget, Lyon admitted that there would be downward pressure from member states facing their own economic crises but believed that the benefits from a robust CAP far outweighed any reason to reduce the cash in this particular part of the EU budget."

Screw the CAP, man. It's just a prime example of a policy that benefits nobody. It's like a canker on the rotting corpse of European policy. What the hell are the benefits from it? There are zero Goddamn benefits, except for a few fat-arsed dole-blodging millionaire farmers.

Robust CAP? Gag me with a spoon.

I think it's time for breakfast.

"In looking at the EU budget, Lyon admitted that there would be downward pressure from member states facing their own economic crises but believed that the benefits from a robust CAP far outweighed any reason to reduce the cash in this particular part of the EU budget."

Screw the CAP, man. It's just a prime example of a policy that benefits nobody. It's like a canker on the rotting corpse of European policy. What the hell are the benefits from it? There are zero Goddamn benefits, except for a few fat-arsed dole-blodging millionaire farmers.

Robust CAP? Gag me with a spoon.

I think it's time for breakfast.

Friday 2 July 2010

Monday 17 May 2010

Straight people having gay marriages

Very interesting article here. Interesting comments too. Re my previous blog post... does marriage-lite help or hinder commitment?

Saturday 8 May 2010

What's good for the goose...

I'm a Thatcherite. I believe in the magic of competition. I just can't help it. When I see an overregulated industry with a few lazy, inefficient incumbents, I instinctively think "tear down the barriers to entry!"

That should apply to politics too. What Britain has had for 60 years is a two-party duopoly. People are now sick of both parties. It would be much healthier if they faced some bracing competition from smaller, nimbler players. We should tear down the main barrier to political entry, which is the First Past The Post electoral system. Demand a referendum on PR now!

That should apply to politics too. What Britain has had for 60 years is a two-party duopoly. People are now sick of both parties. It would be much healthier if they faced some bracing competition from smaller, nimbler players. We should tear down the main barrier to political entry, which is the First Past The Post electoral system. Demand a referendum on PR now!

Thursday 6 May 2010

Money well spent?

"The immediate political liability for this lies with Mr. Brown and the Labour Party, which engaged in a spree of epic proportions after taking power in 1997, spending at a rate that has outstripped inflation by 41 percent. The current budget of about $1.1 trillion includes more than $150 billion on the state-run National Health Service, triple the amount when Labour came to power.

One in every four pounds the government spends is borrowed, a pattern that economists say will require the next government to make cuts on a scale not experienced since the Great Depression, as well as painful tax increases."

One in every four pounds the government spends is borrowed, a pattern that economists say will require the next government to make cuts on a scale not experienced since the Great Depression, as well as painful tax increases."

Wednesday 5 May 2010

The dilemma

The Lib Dems are loons. Their policies are a mix of the interesting and the bloody silly. In the ordinary course of politics, sometimes the main parties nick their best ideas. I would not be thrilled to experience their worst ones. And Nick Clegg... well, to me he seems like a blank space on to which the electorate are projecting their hopes. Mr Not The Other Two.

But the Lib Dems are loons *because* of the two party system. If you want to go into government, you have to join the Tories or Labour. The Lib Dems get the leftovers. If they had more chance of getting into office, they would attract more talented politicians. Electoral reform would let that happen. And liberal ideas -- the deep underlying ones, not the wacko policy proposals -- are pretty decent ones. Liberalism is more alive as a set of ideas than anything Labour has got.

So, do you vote for the loons now, in the hope of getting something better later?

But the Lib Dems are loons *because* of the two party system. If you want to go into government, you have to join the Tories or Labour. The Lib Dems get the leftovers. If they had more chance of getting into office, they would attract more talented politicians. Electoral reform would let that happen. And liberal ideas -- the deep underlying ones, not the wacko policy proposals -- are pretty decent ones. Liberalism is more alive as a set of ideas than anything Labour has got.

So, do you vote for the loons now, in the hope of getting something better later?

Saturday 1 May 2010

Election thoughts 2

Dream: a Tory - Lib Dem alliance. Clegg forces electoral reform on to the agenda and we get a referendum between the status quo and some moderate form of PR like the Alternative Vote system. Vince Cable becomes chancellor instead of that little pink feller Osborne. Tory radicalism on education is tempered with a concern for equality. The Libs' dafter ideas are sidelined.

Nightmare: a Lib-Lab alliance. Labour have austerity for two years, then resume pouring money into the public sector. It doesn't work, of course, and public cynicism extends to include the Lib Dems. We gradually become more like a normal European economy - slow-growing, sclerotic and riven by the populism of an embittered majority.*

In between these I would obviously prefer Tory to Labour.

Quite a tough choice therefore - go for strengthening Clegg's hand or play it safe and vote Tory?... Anyway, I voted by post so now it's up to you lot.

* [purple passage]

Nightmare: a Lib-Lab alliance. Labour have austerity for two years, then resume pouring money into the public sector. It doesn't work, of course, and public cynicism extends to include the Lib Dems. We gradually become more like a normal European economy - slow-growing, sclerotic and riven by the populism of an embittered majority.*

In between these I would obviously prefer Tory to Labour.

Quite a tough choice therefore - go for strengthening Clegg's hand or play it safe and vote Tory?... Anyway, I voted by post so now it's up to you lot.

* [purple passage]

Saturday 10 April 2010

Monday 5 April 2010

Leaving the uk tomorrow

Been weird coming back here. The place feels like it's waking up with a hangover, from a party which turned really sour. Atmosphere of congealed greed and mistrust. (Not wanting to go overboard here. But.)

Wednesday 31 March 2010

General election

I've been wavering between the Lib Dems and the Tories. (1997: Labour. 2005: Lib Dem.)

The Lib Dems:

+ have Vince Cable who made the right calls before and during the economic crisis. I wish he could be chancellor

+ want electoral reform, which may well be a good idea

- do not seem very coherent

+ have a strain of liberalism

- have a strain of social democracy

+ opposed the war

The Tories:

+ are broadly pro-market, which I think is in general a good thing, despite the financial crisis

- David Cameron has a character issue. I do not get the feeling he has much strength of will or very clear ideas

+ ... but I liked his conference speech, which made devolution of power the central theme

- have too many Old Etonians. Class privilege is bad

- ... in particular George Osborne, who does not seem to know his job

- ... and their response to the financial crisis was not impressive

+ want the Swedish schools reform. Education is the biggest issue for me

+ seem to have some smart people on their team (Hague, Willetts, Gove)

I now intend to vote Tory, after reading the Lib Dems' education policy. (It's incoherent. Their diagnosis is "too much central control", and their cure is "give power back to Local Education Authorities". Gove's plan is much better.)

The Lib Dems:

+ have Vince Cable who made the right calls before and during the economic crisis. I wish he could be chancellor

+ want electoral reform, which may well be a good idea

- do not seem very coherent

+ have a strain of liberalism

- have a strain of social democracy

+ opposed the war

The Tories:

+ are broadly pro-market, which I think is in general a good thing, despite the financial crisis

- David Cameron has a character issue. I do not get the feeling he has much strength of will or very clear ideas

+ ... but I liked his conference speech, which made devolution of power the central theme

- have too many Old Etonians. Class privilege is bad

- ... in particular George Osborne, who does not seem to know his job

- ... and their response to the financial crisis was not impressive

+ want the Swedish schools reform. Education is the biggest issue for me

+ seem to have some smart people on their team (Hague, Willetts, Gove)

I now intend to vote Tory, after reading the Lib Dems' education policy. (It's incoherent. Their diagnosis is "too much central control", and their cure is "give power back to Local Education Authorities". Gove's plan is much better.)

Saturday 6 February 2010

A million monkey puns.

Political scientists worry about democracy because voters are rationally ignorant. That is, since you are unlikely to decide any election on your own, it doesn't make sense to learn about political issues which you cannot affect. This theory is supported by a lot of evidence: most people really don't know very much about politics. (Even hardworking political scientists.)

Democrats respond with an argument that goes back to the Marquis de Condorcet. Even if no individual voter knows much, they are still likely to make the right decision. For example, think of a jury deciding whether to convict someone. Even if every individual on the jury is only a little bit more likely to be right than wrong, when they all vote together, the majority is quite likely to come out on top. And if millions of people were on the jury, then the right decision would almost certainly be made. The famous political scientist Skip Lupia put it like this: unless voters are Dumber Than Chimps, they are likely to make the right decision in the aggregate.

So, by this Condorcet Jury Theorem, democracy should work quite well. It's a bit like one of those stories where a million monkeys (or chimps) bash away at typewriters and one of them eventually produces Hamlet. Voters may not know much, but on average, they'll get to the right decision. The Theorem works for more complicated decisions than simple guilty/innocent choices. Suppose we vote on how much to spend on hospitals. Different people have different views, some of them quite wacky, but on average, the median voter is just right. Half the people want to spend too little, and half want to spend too much. If so, then a proposal to spend exactly the right amount will beat any other proposal. (If the other proposal is lower, at least half the voters will prefer the higher amount; if it's higher, at least half will prefer the lower amount.) And a political candidate who promises to spend the right amount will make a monkey out of any other candidate.

However, I think the Jury Theorem is completely bananas.

First, it depends on the idea that people are right on average. But there is no reason to expect that. Remember, people are wrong because they are uninformed, because informing yourself would be costly. Bob Dylan's The Hurricane is a song about Rubin Carter, a black man wrongly accused of murder:

Almost everybody thought that Carter was guilty. Of course, a little investigation would have uncovered serious flaws in the case against him. But in a big jury vote, nobody has the incentive to do the investigating - it was left up to a few public-spirited journalists and activists. Uninformed people will not, in general, be right on average.

The other gorilla in the room is that even if people's views are right on average, they may not choose the right policy on average. This is a little subtler, so if maths makes you go ape, you can skip the next bit. Suppose we are deciding how much to spend on defence, and we face a national rival. We aren't sure about this rival's political ideology: is it to the left of us like Soviet Russia? Or to the right like Nazi Germany? (Maybe it's modern China.) The farther it is from us, the more we ought to spend.

In fact, our rival has just the same ideology as us. We need to spend almost nothing. And "on average", people know this. But their views vary - some people think that our rival is leftist, some people think its rightist. So, if we vote on military spending, we would end up spending quite a hairy amount. The voter with the middle estimate of the other country's ideology, who correctly thinks we should spend nothing, is right at the bottom in terms of the spending he wants.

Of course, if we voted on the facts of the matter, we would get them right. But in practice, most policy decisions depends on hundreds of facts, and there's no practical way we could vote on them all. So, even if people were miraculously right about all the facts - on average - they wouldn't necessarily choose the right candidate, or make the right policy decisions.

To sum up, if you put a million monkeys in a room, you might end up with Shakespeare. But you might just end up with a banana fight and a lot of faeces throwing.

Democrats respond with an argument that goes back to the Marquis de Condorcet. Even if no individual voter knows much, they are still likely to make the right decision. For example, think of a jury deciding whether to convict someone. Even if every individual on the jury is only a little bit more likely to be right than wrong, when they all vote together, the majority is quite likely to come out on top. And if millions of people were on the jury, then the right decision would almost certainly be made. The famous political scientist Skip Lupia put it like this: unless voters are Dumber Than Chimps, they are likely to make the right decision in the aggregate.

So, by this Condorcet Jury Theorem, democracy should work quite well. It's a bit like one of those stories where a million monkeys (or chimps) bash away at typewriters and one of them eventually produces Hamlet. Voters may not know much, but on average, they'll get to the right decision. The Theorem works for more complicated decisions than simple guilty/innocent choices. Suppose we vote on how much to spend on hospitals. Different people have different views, some of them quite wacky, but on average, the median voter is just right. Half the people want to spend too little, and half want to spend too much. If so, then a proposal to spend exactly the right amount will beat any other proposal. (If the other proposal is lower, at least half the voters will prefer the higher amount; if it's higher, at least half will prefer the lower amount.) And a political candidate who promises to spend the right amount will make a monkey out of any other candidate.

However, I think the Jury Theorem is completely bananas.

First, it depends on the idea that people are right on average. But there is no reason to expect that. Remember, people are wrong because they are uninformed, because informing yourself would be costly. Bob Dylan's The Hurricane is a song about Rubin Carter, a black man wrongly accused of murder:

"To the white folks who watched he was a revolutionary bum

And to the black folks he was just a crazy nigger

Noone doubted that he pulled the trigger"

Almost everybody thought that Carter was guilty. Of course, a little investigation would have uncovered serious flaws in the case against him. But in a big jury vote, nobody has the incentive to do the investigating - it was left up to a few public-spirited journalists and activists. Uninformed people will not, in general, be right on average.

The other gorilla in the room is that even if people's views are right on average, they may not choose the right policy on average. This is a little subtler, so if maths makes you go ape, you can skip the next bit. Suppose we are deciding how much to spend on defence, and we face a national rival. We aren't sure about this rival's political ideology: is it to the left of us like Soviet Russia? Or to the right like Nazi Germany? (Maybe it's modern China.) The farther it is from us, the more we ought to spend.

In fact, our rival has just the same ideology as us. We need to spend almost nothing. And "on average", people know this. But their views vary - some people think that our rival is leftist, some people think its rightist. So, if we vote on military spending, we would end up spending quite a hairy amount. The voter with the middle estimate of the other country's ideology, who correctly thinks we should spend nothing, is right at the bottom in terms of the spending he wants.

Of course, if we voted on the facts of the matter, we would get them right. But in practice, most policy decisions depends on hundreds of facts, and there's no practical way we could vote on them all. So, even if people were miraculously right about all the facts - on average - they wouldn't necessarily choose the right candidate, or make the right policy decisions.

To sum up, if you put a million monkeys in a room, you might end up with Shakespeare. But you might just end up with a banana fight and a lot of faeces throwing.

Wednesday 20 January 2010

Myths

Bryan Caplan surely had bad luck with the timing of his book "The Myth of the Rational Voter", which argues that voters are irrational because they don't think like economists, and that we should trust markets relatively more. (I am caricaturing.) It came out in April 2007. Two years later, economists' credibility has been battered, and the policy of trust in markets has got as much legs as a paraplegic snail. A shame, because he has some interesting points.

Tuesday 5 January 2010

Thoughts

When I was younger, I assumed only poor people had children without getting married. Now I have reached the age where friends of mine are having children. Either I was mistaken, or my generation's behaviour is different. I know a lot of couples who have had children out of wedlock. The circumstances varied. Sometimes couples decided to have a child without getting married. Sometimes a girl got pregnant accidentally and decided to keep the baby. Then the man stayed with her but without marriage, or left.

Everybody has their own life to live. It is easy to moralize, but much harder to live up to your own moral standards, or other people's.

Still, I am worried about this change. It is better for a child to have two parents who are committed to each other. Because people's feelings are very variable, it is better to commit to each other with a public promise. If two people are not ready to make that public promise, then I do not think it is the right time for them to have a child.

This issue evokes strong feelings in me because of my own family history. Other people with different stories might have different feelings. All these emotions deserve respect, but they do not replace facts. The claims I have just made are in line with the social science evidence. Children from married parents have "better outcomes" than children living with two unmarried parents, or with single parents. That jargon term means that they are happier, do better in school and so forth. (I am not an expert in this area and the science is no more settled than in any other social science topic. Google Scholar has been my friend here.)

There are many reasons why people's choices about marriage have been changing. Two important ones may be culture and laws.

Up until the 1950s, sexual and family culture was not very free. There were a whole set of rules that applied to people. Sometimes these rules were enforced by formal institutions: for example, unmarried mothers might be forced to give up their children for adoption. But I believe that mostly they were enforced by social pressure. People who broke the rules could be shunned by their peers. Many of these rules were unjust. Different standards applied to men and women. Gay sex was seen as wrong and gay people were stigmatized. In some places even interracial marriage was disapproved of or banned. The rules were mainly justified by religion.

In the 1960s, more people started to reject these rules, for all sorts of reasons but partly

because they thought they were unfair. Since then, it has widely been thought wrong for us to judge other people's behaviour by any rules. Of course, many things are agreed to be bad (like murder and defrauding old ladies). But there used to be a big layer of behaviours classified as not illegal, but immoral. That layer, between the illegal and the totally OK, has got thinner.

Everybody has their own life to live. It is easy to moralize, but much harder to live up to your own moral standards, or other people's.

Still, I am worried about this change. It is better for a child to have two parents who are committed to each other. Because people's feelings are very variable, it is better to commit to each other with a public promise. If two people are not ready to make that public promise, then I do not think it is the right time for them to have a child.

This issue evokes strong feelings in me because of my own family history. Other people with different stories might have different feelings. All these emotions deserve respect, but they do not replace facts. The claims I have just made are in line with the social science evidence. Children from married parents have "better outcomes" than children living with two unmarried parents, or with single parents. That jargon term means that they are happier, do better in school and so forth. (I am not an expert in this area and the science is no more settled than in any other social science topic. Google Scholar has been my friend here.)

There are many reasons why people's choices about marriage have been changing. Two important ones may be culture and laws.